Pink Iguana, April 2009, Essay

For position only

n. Abbr. FPO

A publishing term for a low-resolution image used as a temporary place-holder for the high-resolution version which will be used for printing.

*

I’m in the photography gallery at MoMA to see Into the Sunset, the American West as seen through the eye of the lens. It’s Good Friday and I’m weaving my way through the throng of European Easter tourists and chattering children.

I’ve been captivated by the portrait of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, like a faded school panorama, and of Butch Cassidy and his gang, suited and booted and looking rather stuffy. I’ve been unsettled by Robert Adam’s portrayal of domestic dislocation and Larry Sultan’s sinister suburbia, moved by pristine landscapes and broken dreamers.

But for several minutes when I first come across it, unaware it would be there, I can see only one picture.

It’s David Hockney’s photomontage Pearblossom Hwy., 11-18th April 1986, #2 and for those few moments a million memories flood my head and my heart and I can barely move.

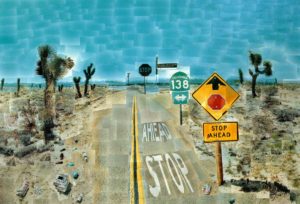

The picture is one of the great American landscapes: the vision of an empty road cutting through the desert and disappearing into the distance. It was constructed by the artist from over 700 individual photographs, shot over several days at a junction on Pearblossom Highway in California’s Antelope Valley.

It’s a picture I know so well, and yet until last Friday, didn’t know at all.

I first came across Pearblossom Hwy in the autumn of 1989. I was back in England after a long summer in Spain. I’d gone to Barcelona to learn some Spanish, a condition of changing my degree course. After three days at a youth hostel I’d found a room in a pension in the Barrio Chino. Today the Chino is desirable, but in 1989 it was awash with prostitutes, drugs and muggers. My US guide book was advising to steer well clear by day and by night to risk certain robbery, death, and whatever else it is that happens to nervous mid-Western tourists.

The other residents, like me, were all there for the long-term, a variety of Brits and Americans. Most were teaching in the private language schools or modeling for adult art classes. (I tried both when my beer money was running low.) Far from learning Spanish, I spent my nights up on the roof, drinking, smoking, listening to the boys play guitar, considering sex with the latest American arrival, my days largely lost sleeping it off.

One afternoon Maria appeared. I’d never met a genuine New Yorker before. I was from London and thought myself sophisticated enough but she was something else. Three years older than me, wise, beautiful, stylish in that particular ‘80s New York street way, first generation naturalised Greek-American with an artist’s sensibility, canny survival instincts and the sharpest tongue deployed in cases of injustice – I would never have dared wrong her.

Sometimes the normal process of coming to know someone accelerates. The weeks, months, years of discovering what another person’s like is condensed into an instant. And just as the knowing comes, inexplicably, out of nowhere, so too does the love.

It’s happened like that just a few times in my life, and that’s how it was with me and Maria. We’d known each other 24 hours when we resolved to leave Barcelona together and go traveling. I can’t remember whose idea it was to hitchhike across Spain to Portugal – probably hers, but I’d have needed no persuading.

Although there was never a low point during our road trip there were plenty of incidents. A few hours into our first ride, while we were eager to get underway, a creepy young lorry driver claiming he needed to rest pulled into a layby to see which one of us he could seduce. (Neither, needless to say.)

Later there was an alarming hour in the back of a minivan when we were both gripped by the same sense of dread. The driver eventually agreed to let us out – I don’t want to think what might have happened if he hadn’t – leaving us on a deserted stretch of road in the worst heat of the day.

In a tiny town in Portugal, where the only room we could find was in a brothel, we stashed our passports under the mattress for security, remembering them only the next afternoon, 100 miles further down the coast.

Mainly though it was exhilarating. It was freedom. I was 20 years old, no longer a teenager straining to reach adulthood, sharing adventures in light-headed companionship. So this was how it was going to be.

As a pink dawn broke over the Meseta Central, sat up high in the cab of a 12-speed juggernaut, I took the wheel – the only human stamp on that arid landscape was the tarmac stretching out ahead and a single steel bull on a distant hill.

Drifting back at 4am from a night of dancing in Madrid’s hottest club, we picked up the scent of warm chocolate and cinnamon that led us to a night-owls’ haven, a churrisco Shangri-La we could never find again.

We met a group of Spanish journalists as we crossed into Portugal who made us honorary members of their film crew – though I imagine they called us contacts or interviewees on their expenses claim.

One harmless, middle-aged Portuguese lift invited us, with grins and graphic gestures, to join him in a threesome. He was unsurprised when, through fits of laughter, we turned him down. He can’t have expected we’d say yes, but even though the odds were stacked sky-high against him he couldn’t let the moment pass – two bare-legged foreigners, right there in his truck – without at least asking. He showed there were no hard feelings by giving us his favourite folk music tape.

Far and away the most astonishing thing about that trip was the unconditional generosity of the people we met. We asked for very little – just a ride as far as they could take us – but received so much more. They gave us food, drink, advice. They drove miles out of their way for us. An English couple, worried about dropping us off late at night, insisted we camp with them. He slept outside so we could share the tent with his wife.

When we got back to Barcelona things had moved on. The Algerian who ran the pension was a volatile character who had picked a fight with one of our friends and fallen out with the rest. Summer was ending, people were dispersing.

There was one more trip north along the coast to Salvador Dali’s house and a miserable stay on a once beautiful island that had been squatted and trashed by drugged up Germans who couldn’t decide if they were punks or hippies. And then Maria was gone, back to New York, and I was home too and university life resumed in Manchester in a house with two art history students. Which is how I came across a Hockney monograph and a reproduction of Pearblossom Hwy., 11-18th April 1986, #2.

Hockney has said of his most successful photomontage that it’s about the different experience of driver and passenger. The driver’s vision of the road to the right is filled with signs and instructions while on the left the passenger’s eye is free to wander, taking in instead the open land, the Joshua trees, the debris left at the side of the road by careless humans.

Perhaps that’s one reason I’m drawn to it – sometimes you want to be driven, sometimes you want to drive, in all areas of life. Sometimes too you need to focus on following the signs, while at others to drift and see where you end up.

Mostly though I love Pearblossom Hwy because it takes me back to the open road, to Spain with Maria, and to all the other trips I’ve made since.

Does the stop sign dilute the optimism? I don’t think so. Maybe Hockney meant it to signify the end of the mythic West as repository for America’s dreams, or maybe it’s a witty comment on the mismatch between rules and context. Either way, the lure of that vanishing perspective is stronger than any bossy bureaucratic signage. They can throw as many stop signs as they want at us, for freedom and adventure we’ll drive through all of them.

The same colour photocopy I made of the picture back in 1989, stuck on various walls over the years, is part of my compendium of loved objects. It’s one of the few things I brought when I moved to New York.

And on Friday, for the very first time, I saw the original.

For a start I was struck by how big it is: 9ft x 6ft. Though if I’d thought about it properly I’d have realised it would be so, since each of the 700 odd photographs is a standard size print, processed during Hockney’s 9-day excursion in a local photo booth. For the first time too I could see the mechanics of how each piece is layered onto the next, in some places involving complex cutting and weaving together.

The colour is also different. The sky in particular is so much lighter than I’ve always known it. Should I assume that’s how it’s always been? Hockney, who held the piece in his personal collection until 1997, only agreed to sell it to the J Paul Getty because the museum had the means to protect it from colour fade. But maybe by then it had already lightened over time. Perhaps my reproduction is closer to Hockney’s original intention.

There’s another meaning that saturates the picture. In all his photo-collages, of which Pearblossom Hwy was the last and the largest, Hockney was exploring the limits to representation. Drawing on cubism, the picture plays with multiple perspective, the individual photographs of which it’s made up intentionally disjointed to express the fluidity of perception. The pertinence of knowing only through reproduction, a work of art so concerned with the very nature of reproduction hadn’t occurred to me until Friday.

From now, when I think of Hockney’s great American landscape it will be the 9ft x 6ft Pearblossom Hwy., 11-18th April 1986, #2 on the wall of MoMA, not the tattered photocopy I’d come to think of simply as Ahead Stop. In my mind’s eye, the FPO image has finally been replaced by the genuine article.

In a day of small but accumulative serendipities, it occurred to me that I’ve been going through a scaled-up version of that very same process every day since I moved to NYC. For a few years after Spain I used to come here to stay with Maria in the East Village. For nearly two decades I’ve carried around a picture in my head of this city and the people I knew then. As I start to establish my life here now, reconnecting with old dreams and old friendships and discovering new ones, I’m gradually swapping, section by section, my place holder image of New York City with the real thing, like the individual shots in my own photomontage.