Crafts Magazine, Feature, November 2011

What does it mean to buy a book anymore? A visit to the bookshop, or a click of the mouse? And what is a book now anyway? A bound paper codex, or the bits and bytes stored on your e-reader? Maybe soon enough, the old-fashioned, physical book will go the way of the CD (remember those?), but publishers aren’t giving up without a fight. Which is why, surprising as it sounds, Penguin’s creative director Paul Buckley says his job is more fun than ever. ‘I used to go upstairs and say I want to do this and it’s going to cost all this money and they’d say, “Paul, we don’t need all that production.” Now they’re saying, “Yes you’re right, let’s make it as gorgeous as we can.”’ To sell people books they can download for free, you have to offer them truly desirable objects.

Most recently, Buckley (full title vice president executive creative director) has been having fun with Penguin Threads, a series of hand-embroidered covers for Penguin Classics. The first three – whimsical yet modern interpretations of three of Penguin’s best-selling, most beloved stories – were created by New York-based illustrator Jillian Tamaki and go on sale in November.

The idea for Threads came to Paul Buckley during a lunch hour. Looking around crafts site Etsy, he found a woman selling embroidered mermaids. ‘The mermaids were really beautiful, under the ocean, with seaweed floating up around their heads. I bought one for 37 bucks.’ When the piece arrived he showed it to Elda Rotor, editorial director for Penguin Classics. Rotor was thinking of ways to market the classics to the ‘hand-made craft-loving Etsy crowd’ – the antithesis, as she sees it, to the digital-savvy mob. She was instantly onboard.

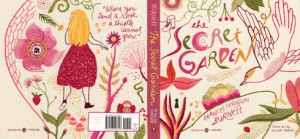

‘And Elda said, “You’re right, it’s a book series.”’Rotor chose the titles: Emma by Jane Austen, The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett and Black Beauty by Anna Sewell. Three big hitters from Penguin’s back list, the sort of all-time favourites that Rotor imagines being passed on to the next generation, given to loved ones, and commanding a prominent place on the shelf. The sort of books that deserve to be made into gorgeous, coveted objects. Buckley, meanwhile, set out to find illustrators who could sew.

He chose Tamaki – who he knew already as a comic-book artist – almost by accident. He was bouncing around illustrators’ websites, looking for someone to design a set of Jack Kerouac covers, and was stopped short by a photo of her Monster Quilt. ‘I rolled down Jillian’s blog and the last thing on the front page was this beautiful embroidered quilt. It was a sort of eureka moment. This is her! This is the person I need.’It was shortly before Christmas, and Buckley needed the work completed by February, a fast turn-around. He offered Tamaki a single title – she could take first pick – thinking he still needed two more illustrators, but Tamaki convinced him she could take on all three. ‘It was over the Christmas holiday and I said, “You know, I’m gonna need these in a couple of months and I’m not so sure you can do it.” And she said, “I can.” Basically, she talked me into it.’

The Monster Quilt – a delightful montage of colourful, imagined monsters – was Canadian-born Tamaki’s first experiment with embroidery. Since graduating from Alberta College of Art and Design in 2003, she has worked as a freelance illustrator on comics and graphic novels, as well as for such newspapers as the Guardian, and the New York Times. Last year, interested to learn how to sew, she began the quilt – a freeform sampler to teach herself stitches from a book of embroidery techniques. Tamaki is first to admit she’s no professional seamstress. But her experience as an illustrator gives her embroidery a powerful graphic quality. ‘I like to think that what people are reacting to is the drawing beneath the stitches,’ she says.

The Monster Quilt – a delightful montage of colourful, imagined monsters – was Canadian-born Tamaki’s first experiment with embroidery. Since graduating from Alberta College of Art and Design in 2003, she has worked as a freelance illustrator on comics and graphic novels, as well as for such newspapers as the Guardian, and the New York Times. Last year, interested to learn how to sew, she began the quilt – a freeform sampler to teach herself stitches from a book of embroidery techniques. Tamaki is first to admit she’s no professional seamstress. But her experience as an illustrator gives her embroidery a powerful graphic quality. ‘I like to think that what people are reacting to is the drawing beneath the stitches,’ she says.

For the Threads covers, Buckley allowed her to interpret the books as she saw fit. ‘I had the freedom, to make them colourful, flat and graphical and not historical. I wanted them to feel timeless, but quite different.’ She used a Wacom Cintiq, a digital drawing board, to sketch out the thread strokes and colour combinations. Once Buckley had approved the designs, she began stitching, mainly with crewel techniques. Unlike the crewelwork in the Jacobean tapestries for which it was invented, Tamaki used lightweight muslin and thread. Several times she had to start afresh after damaging the cloth irreparably by unpicking and correcting as she figured out how to achieve the effect she was after. ‘I’d think of all these things I could do and that I was being so clever, and then I’d get the book out and they’d all be in there – stitches people had already named. I realised I wasn’t so clever after all.’

Of her three designs, The Secret Garden is the most romantic: a montage of twisting vines, unfurling foliage, and fantastical flowers like some magical reimagination of a traditional English garden. On the back cover, striped pink and yellow mushrooms line the dotted suggestion of a path and the figure of a girl is seen from behind, with thick strawberry blonde hair and a dress of richly-textured carmine. Here and there are seeds, a ladybird, a caterpillar – the garden seen through a child’s eye – along with symbols from the story, such as a blackened keyhole and an Edwardian laced boot. With its palette of lush pinks and vibrant greens, it feels fertile, full of hope and possibility, and a little wayward.

For Emma, Tamaki produced a simple portrait. The heroine’s refined features are offset by strands of multi-coloured twisted hair in couching stitch, arranged under a bonnet with a decorative pink bow floating beneath her chin. If it brings to mind Milton Glaser’s famous Bob Dylan poster, Tamaki is fine with that, since there’s a touch of the rock star in Austen’s ‘handsome, clever and rich’ Emma Woodhouse.

Of the three books, Tamaki felt most connected to Black Beauty, having ridden as a teenager: ‘At that time, horses were pretty much all I drew.’ In contrast to the colourful exuberance of the other two, her portrait of the horse is monotone, but full of movement and energy. The horse’s mane is made up of loose threads, knotted in the back and pulled through the cloth and its body is a freeform pattern to represent his emotional inner life.

When Buckley saw the finished embroideries, he was bowled over. ‘They were just stunning, it was mindblowing. I ran upstairs to show Elda and then I ran into my publicity department and said, “You guys need to go nuts with these.” Everyone just got behind it because they were such objects.’

But the very first thing Buckley did, even before showing them to his colleagues, was to email Tamaki requesting to buy one. ‘I really wanted to own one but the price was outrageous, four or five thousand dollars.’ Though actually a fair one, he concedes, considering the time and work that went into them. ‘Yeah, I get it. I was just hoping she’d be naïve about what they’re worth – unfortunately she’s very intelligent.’

To create a genuinely embroidered cover for every individual book would be prohibitively expensive. So to reproduce the texture of the stitching, Buckley first had Tamaki’s originals photographed at a resolution of 900 dpi (dots per inch), rather than the industry standard of 300. ‘I spent a fortune on photography.’ The stitching was then sculpt-embossed to mimic the rise of the thread. Buckley, aware that embossed covers can look tacky (think airport chick lit) had proofs made up first, rather than go straight to final printing. As it turned out, the embossing works beautifully – detailed, subtle, tactile – and goes some way to reproducing the quality of real thread.

At a certain point before the printing stage, Buckley had another eureka moment. Tamaki had attached felt backing to the original embroideries and out of curiosity one day Buckley peeled back the felt to peek at the reverse stitching. What he found was so fascinating he decided to use it as the image on the inside covers, behind the french flaps. A little to Tamaki’s horror: the covers are attracting attention from experienced embroiderers, who will be able to see all her fluffs and errors. ‘The purist in me thinks the back should be just as beautiful as the front, all neat and tidy, but these are a mess. When you’re working digitally, you can tweek and tweek and erase and erase forever. Working in this medium nothing has to be perfect, it just has to stand. Ultimately, I suppose, that adds life and nuance and individuality.’

While the enforced discipline of stitching has helped Tamaki simplify her drawing and develop her illustration skills, it won’t become a new direction for her. It’s far too time consuming, she says, a single line takes her half an hour to produce. Her next project will be another graphic novel.

Buckley, meanwhile is working on the next three embroidered covers in the Threads series: The Wind in the Willows, Little Women and The Wizard of Oz by illustrator Rachell Sumpter. Once those are complete, he may continue with embroidery, or mix in some crocheted covers. ‘As long as we’re enjoying the process there’s no reason not to do them. We’ll keep on going, for as long as it’s fun.’